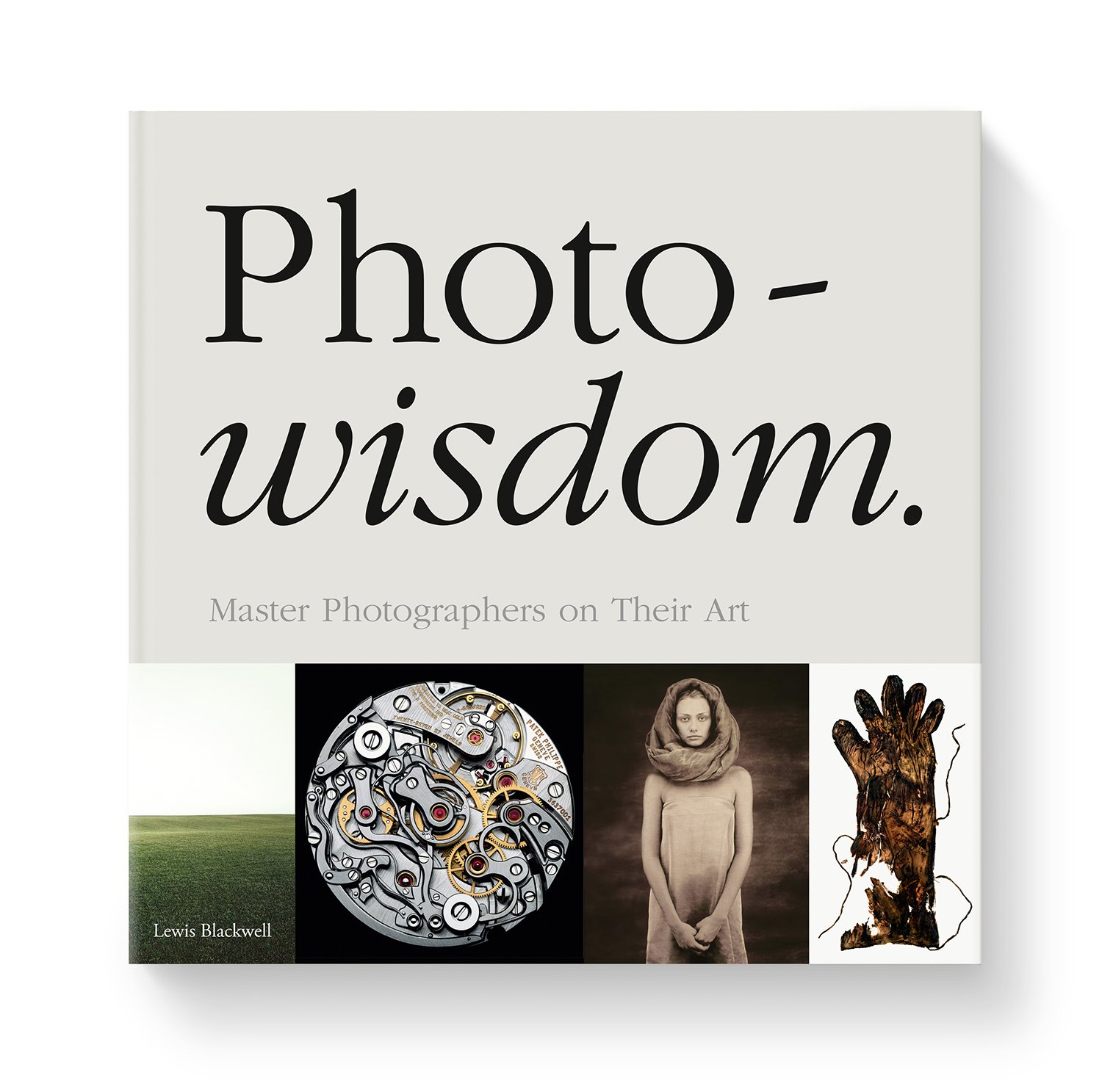

Master Photographers on Their Art

Taking a picture was initially an almost voyeuristic thing. At the beginning I was not given the opportunity to do big projects, but I would be commissioned to go and photograph somebody or something. These jobs could be as diverse and everyday as recording a factory pickling gherkins or shooting a portrait of a designer of a new bike – but it allowed me to go into different worlds, expose myself to different things. Then I started to see how photography was a way of creating a doorway for somebody else to find other things. You can have signs in the image that have a potential to take people somewhere else. You may not understand everything that is there, but you can have a sense for it. So I might have an image of a neck of a horse: at one level it is a horse, in another way people might see it more as a mountain, but having heard people discussing it, I see they can find other asso- ciations. Photographs have this potential for layering, many interpretations, ambiguity, which makes photography very special. But still it has this ultimate strength, in that some- thing existed at some point in front of the lens; if that ingredient is maintained, respected, then you have the potential for people to find a lot of connections out of that original moment that you may never have anticipated, that you could never anticipate.

A painting has texture, an artist constructs something. A photograph is this and yet also something different. A photographer sees something – you do not simply create and you do not just look. You observe things like a fine artist and you make something too, but you do it in a real space and clearly share your journey with the viewer. You are both moving around, looking into a real space that existed, that the viewer understands you to have photographed.

How you see the observer of the image is so important. Where this person is, where the image is: it’s almost everything. I consider who is seeing the picture and if it is being delivered on a website, in an exhibition, in a book or other print. I have done images for stamps, which obviously have a very special frame of reference, not to mention being small in size. I have to think: “Will there be the means to support the image with other information? Will the viewer be affected by other things?” It is important to consider what is possible, within the image and around the image. Understanding how it will be perceived is important. I am not a photographer who just does an image and thinks, “That is it. Now the viewer can make of it what they will.” You can take a lucky picture – it can work – but it is better if you take a true interest in how the communication works, how the photograph will transform somebody’s experience, how meaning will be achieved.

If I take the subject matter of my bats, the series where the image is turned upside down, then I think people are surprised to find how easily they engage with a perceived “personality” in the bat through the turned-around image. At one level it is a simple trick, but it transforms the experience. Another image where I make a simple shift that transforms the viewer experience is where I have photographed a lot of flies on horse shit. This might not be an incredible image, but it is surprising how people are more willing to engage with the subject, appreciate the flies as remarkable things. And this is achieved through the scale being different. The flies are huge and you can see the beautiful iridescence of their wings and suchlike. Or take my image of horse placenta – not normally seen as a subject with aesthetic properties, but I have worked to make something that you do start to be curious and intrigued by, enjoying the architecture, the mapping of the veins, and you may be reminded of leaf-forms by the structure.

You always need some kind of framework to start, but also you need to be open to what you observe. Often the most interesting things are the surprise obstructions that you encounter on your presumed journey. But without the plan, you do not have the framework that gets you inquiring in the first place, or creates the situations where interesting things can happen. The photographer’s surprises become surprises for the viewer, too. You set out to do one thing but are open to changing direction as you see opportunities. When I brought these fruit bats into the studio, I had an idea to fly them around and then retouch them against a night sky. This was not a great idea, particularly as fruit bats are not that wonderful at flying by bat standards. Then I noticed the bats seemed to be almost chatting away together in the corner of the studio where they were hanging. So I opened out to the potential of that, saw something new in the idea of their personalities and the relationship between them rather than the flying, and asked the handlers to bring them back for another day where I could approach it with the fresh objectives. I am often reminded of the Bill Brandt quote, where he said that photographers must see more intensely and reveal a sense of wonderment. (“It is part of the photographer’s job to see more intensely than most people do. He must have and keep in him something of the receptiveness of the child who looks at the world for the first time or of the traveller who enters a strange country.”) This is the idea of really seeing, not just looking. If your reasoning mind distracts you from seeing then you are the poorer: less likely to reveal something that you find intriguing, that resonates.

There is a sense of wonderment about the complexity of nature, and I am often reminded and excited by that with the subject matter I approach. I am in awe of nature, but while my subject may be animal, at the same time I am exploring things to do with what it is to be human.

Respect is due in a big way to the influence of philosophers like Roland Barthes and Vilém Flusser upon photographic practice today, my work included. Barthes has had an extraordinary influence on the generation working now, whether they are conscious of it directly or not. Our idea of the role of the image in our society, the concept of what an image is, owes a lot to philosophers at least as much as image- makers. It feeds back into the image-making.

There is a major “democratization of photography”, as Susan Sontag said. Photography today is a more exciting medium to participate in – there are richer experiences to draw from potential viewers of the work; the technology makes it even more of a medium that people can see and create, can participate in, than it was say twenty years ago. This influences me in how I think about how people view the image. I am aware that the viewer may have already seen a subject intensely, and that others have covered it. Part of my challenge is to defamiliarize the subject. I need to make us see the world as a little strange again, with fresh eyes and new insight. Perhaps I do animals as I do because I see so many people shooting wildlife images, going about documentary work with the subject. I am more interested in how we, humans, are involved in this subject: how we are anthropocentric, inevitably putting ourselves at the centre of any understanding of animals. We also respond to them by imposing our behaviours on theirs, see them as we see ourselves. We anthropomorphize the animal.

From PhotoWisdom: Master Photographers on Their Art by Lewis Blackwell. Copyright by the photographer, reproduced with the permission of the publisher Blackwell & Ruth.

From PhotoWisdom: Master Photographers on Their Art by Lewis Blackwell. Copyright by the photographer, reproduced with the permission of the publisher Blackwell & Ruth.