Master Photographers on Their Art

I did not start with just photography, and I am not ending up with it, as I make films as well, but it has been the dominant expression for me. I went to Harvard, not art school, and studied social studies and then visual anthropology. This gave me a year going around the world studying film and anthropology, living with families in nine countries. I realized I was interested in culture – that was my calling – but I did not know how to express this. I decided I wanted to do filmmaking, applied to film schools and tried to get grants, but nothing worked out. I did this project about the French aristocracy in photographs, and photography proved to be a very accessible medium; I could just take my camera and tape recorder and make pictures and interview people and document how they lived.

So, I did not come into this work as an artist or conceptual image-maker. I was about social documentary, telling stories of how people lived. I got a photo internship from National Geographic. When I went there it was the first time I saw a photographer as a journalist – up to that point I had not taken photography seriously as a career because I thought it was about illustrating other people’s stories. It was the first place where I saw the photographer as the primary storyteller, the one doing the research and telling the story.

There is a tradition of documenting the other, the exotic, in photojournalism. I was told by one of my teachers in college that to start as a journalist you really have to go to a war – that’s how you cut your teeth and get known. I was thinking, “Wow, that’s not for me!” But I started to figure it out when I was at National Geographic. Afterwards I did a project on the Mayan Indians in Chiapas, Mexico, where I worked with my mother who had been researching there for twenty years. We had a connection with the subject, but I felt an outsider struggling with language and access. I had this revelation that I was spending so much time just trying to get to the point where I could even make pictures. I thought if I photographed something I actually knew about and cared about in a deeper way this would be more productive. I started thinking about going back to the place I grew up in and photographing my own experience. I grew up in Los Angeles and moved away for college and lived in a few different places after college. During that time, I realized how interesting, specific and peculiar was the world I grew up in and started to think that might be interesting to document. So, I had this reaction to photographing the exotic and wanted to photograph something I could penetrate more deeply. I started photographing in my own high school and from there the project grew and evolved and took me other places, looking at how kids grow up. It was linked to this understanding from my own background. That is how things took off. When the work came out as a book, Fast Forward, I was able to establish my own voice, or the beginning of one.

Girl Culture, the next project, was not any world I knew directly. I photographed all kinds of girls and women. They might seem like exotic environments – strippers and showgirls and more – and they were areas I had no personal experience with. But each was a stepping stone from the previous. I had spent time in youth culture with Fast Forward and got more interested in this in Girl Culture. Then my next project was Thin, which was about eating disorders, and eating disorders had started to surface in Fast Forward and the obsession with body image had been in Girl Culture. I had been photographing for several years at the eating disorder clinic because of Girl Culture, before I started Thin. So, it was a very organic journey.

I try to spend enough time on projects to really get inside them. With the eating disorder clinic I came into it with a background as Girl Culture had been about how the body had become the primary expression for girls. Eating disorders would seem to be a pathology that relates to that. But I learned that in fact eating disorders are more about a heart of darkness of mental illness than about any media-driven body image. So, I ended up going to a very different place, through immersion, spending about two years in that world, and making a feature- length documentary film and the photography. When I look back now, I realize I started not knowing anything about eating disorders, but I had an opening to get into that world.

I never know where I am going to end up. Focusing on eating disorders was a left turn for me – my work has been more about the mainstream, or about the extremes revealed or commented on by the mainstream. With Thin, it was such a specific, extreme pathology. I knew it was interesting because it was a pathology that mirrored mainstream issues, and there was an access to this severe mental illness that all women could find, because it looked like some of the behaviours of mainstream female life. And so, I knew that there was something interesting there but had no idea if it would pan out creatively or conceptually.

My pictures always had an emphasis on storytelling, and so I was interested in doing a film and suggested a series to HBO. They said let’s do one on eating disorders. This turned into the most intense documentation experience I have ever had; I thought I had close relationships through my photography, but I had never had anything like this, where I was with the same subjects for such a long period and the subjects were in such a vulnerable and changing point in their life. It was an intense relationship both ways. When I finished the film, I felt there were stories I had not been able to tell and that I needed photography to tell. And so, I went back to photography for the next year and a half and made the images for the book and the exhibition.

I now feel more like a documentary artist who uses different media; when I go out and take pictures, I have my camera, but I am often doing video interviews. As I work on my new project I think of film in the mix. The impact of showing Thin was like nothing else I had – twenty or thirty million people saw the film. It reached the public in a way that is very hard to do in photography.

You need to have an outsider perspective to be able to say something about what you are seeing. You also need to be an insider, get access. So, for me it is exciting to walk the fine line between being a member of the media and at the same time trying to deconstruct the media influence, the media creation.

Is there a social and political agenda behind my work? With Girl Culture I did not start it as a feminist, but I came out of it the other side as a feminist. The work is very much a journey: I don’t have an agenda going in, I have an interest, a sense that there is something there to discover or explore, something problematic. But once the work is done, I am thinking about the educational possibilities, the possibilities for dialogue. It is not that I am trying to directly make social change happen through the projects, but I am trying to provoke conversations about the issues that I think are important.

I try to stay very open when I make the pictures. I go for situations that I think will be revealing and a lot of what comes across happens in the editing. When the work is done, I think, “What is this? What am I trying to say? How can it be used?”.

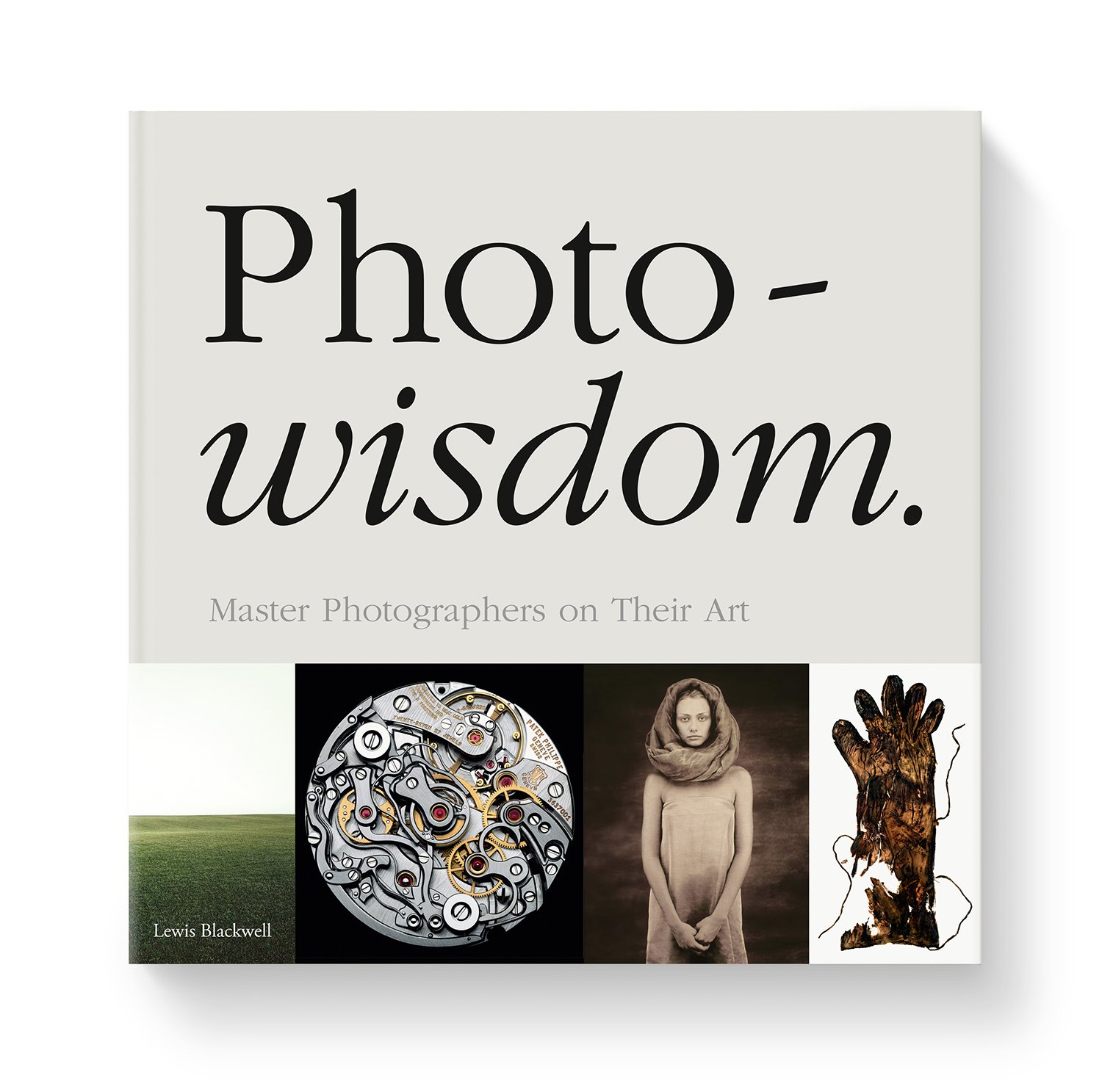

From PhotoWisdom: Master Photographers on Their Art by Lewis Blackwell. Copyright by the photographer, reproduced with the permission of the publisher Blackwell & Ruth.

From PhotoWisdom: Master Photographers on Their Art by Lewis Blackwell. Copyright by the photographer, reproduced with the permission of the publisher Blackwell & Ruth.